Cosesaurus aviceps (Ellenberger and DeVillalta 1974; Ladinian, upper Middle Triassic ~230 mya, ~16cm long), was originally considered an ancestor of birds, then a juvenile Macrocnemus (Sanz and López-Martinez 1984) and finally an ancestor of pterosaurs (Peters 2000b). Here Cosesaurus was derived from a sister to Huehuecuetzpalli and BES SC 111. Cosesaurus was a basal fenestrasaur that phylogenetically preceded Sharovipteryx, Longsiquama and pterosaurs. Once again, as important changes took place, the taxon had a smaller adult size.

Distinct from the BES SC111 specimen attributed to Macrocnemus, the skull of Cosesaurus had a more deeply concave dorsal profile, which further reduced the naris to a long slit. The rostrum was shorter and the postorbital portion was slightly longer creating a larger cranium. The upper maxilla had three openings, together representing the origin of the single antorbital fenestra without a fossa found in derived taxa. The palatine had no lateral process. The parasphenoid was relatively enlarged. The occiput was steeply angled as if the cervicals were typically held further beneath the skull.

The cervicals were shorter, midway in length between those of Macronemus and Huehuecuetzpalli. Four sacrals were present (see below). The caudals were attenuate, as in Macrocnemus.

The scapula was reduced to a a strap-like shape. The coracoid was reduced to a stem-like quadrant shape, resulting from coracoid fenestration, first seen in Huehuecuetzpalli, but further expanded posteriorly until only the posterior quadrant-shape rim remained. The coracoid stem inserted into a socket created by the anterior migration of the sternum to the transverse processes of the interclavicle. In Macrocnemus, as in modern lizards, the disc-like coracoids were free to rotate, but in Cosesaurus they were socketed, as in birds and pterosaurs. If similar in function, that means Cosesaurus was starting to flap its forelimbs long before the advent of a wing-like morphology. This was likely a secondary sexual characteristic behavior that ultimately turned into powered flight in Longisquama and pterosaurs.

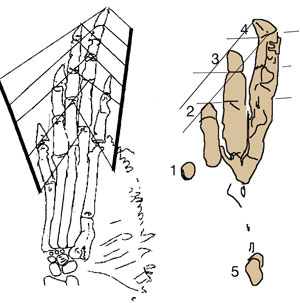

The sternum was broader and displaced such that the anterior rim was coincident with the transverse processes of the interclavicle and clavicles. The clavicles were shorter and only transverse in orientation. They did not extend along the anterior rims of the coracoids and scapula, as in most tetrapods including Macrocnemus. Instead they wrapped around the coincident interclavicle and sternum anterior rims creating the sternal complex otherwise found in Longisquama and pterosaurs (Wild 1993). The interclavicle developed an anterior process making it cruciform. The two centralia had migrated to the medial edge of the wrist where they assumed new identities as the pteroid and preaxial carpal. The manus was much larger, longer than the forearm, with metacarpals and digits less disparate in size except digit V, which was considerably reduced.

The pelvis was considerably shorter with a longer ilium and a much smaller pubis and ischium, which had no space between them. A new bone, the prepubis, extended beyond the pubis increasing its effective length. The proximal tarsals were the same size creating a mesotarsal ankle joint. Metatarsals I-IV were less disparate in length. Pedal 5.1 was elongated, as in Huehuecuetzpalli.

The fossil itself is a mold including no actual bone. The extremely precise negative impressions of every articulated bone, along with an adhering jellyfish and all the soft tissue impressions provide the data and it is subject to misinterpretation, depending on the observers' bias.

Ellenberger and DeVillalta (1974) and Ellenberger (1978, 1993) considered Cosesaurus a bird ancestor, and as such Ellenberger interpreted many aspects of Cosesaurus as proto-avian.

Sanz and Lopez-Martinez (1984) considered Cosesaurus a juvenile Macrocnemus, but it is clear from their report and cartoonish figures they did not put very much effort into their observations.

Peters (2000) saw several pterosaur and Macrocnemus affinities in Cosesaurus but made several mistakes in identification by not identifying the prepubes, the pteroid, the true coracoids and the sternum. That was partially corrected in Peters (2009) with the identification of the pteroid. A paper reinterpreting the pteroid and prepubis was rejected several times on the grounds that Cosesaurus was considered a juvenile Macrocnemus and that pterosaurs were widely considered archosaurs related to Scleromochlus and dinosauromorphs. The rejected evidence is presented below.

Digitigrade, occasionally bipedal footprints attributed to the ichnogenus Rotodactylus (Peabody 1948) were matched to the pes of Cosesaurus (Peters 2000a). Digit V made a small circular impression far behind the other four toes, a behavior unknown outside of the Fenestrasauria. The proximal phalanges were all held elevated, as in pterosaurs, because the metatarsophalangeal joint was a simple butt joint, incapable of much movement.

|

|

Extradermal tissues surrounded Cosesaurus. It had a head crest, dorsal plumes, uropatagia and tail strands. Since it had a pteroid, it is likely that Cosesaurus had a propatagium, a membrane stretching between the shoulder and wrist. The fibers trailing the forelimb demonstrate that the origin of the pterosaur wing began distally unconnected from the hind limbs, not as a gliding membrane close to the body and spanning the limbs like a flying squirrel. Uropatagia trailed the hind limbs. Hair-like fibers emanated from the tail. In some pterosaurs some of these would enlarge and coalesce to form a tail vane.

The very small pelvic opening indicates that Cosesaurus must have laid very small eggs (indicated as an ellipse above). |